- +44 (0)20 8334 8266

- uk@lan-bridge.com

- 中文

What is Mandarin Chinese?

As we discussed last week, the notion that “China speaks Chinese” isn’t as straightforward as it first seems. This week, we will be looking at what exactly Mandarin is – how old it is, where it came from, and what features it has.

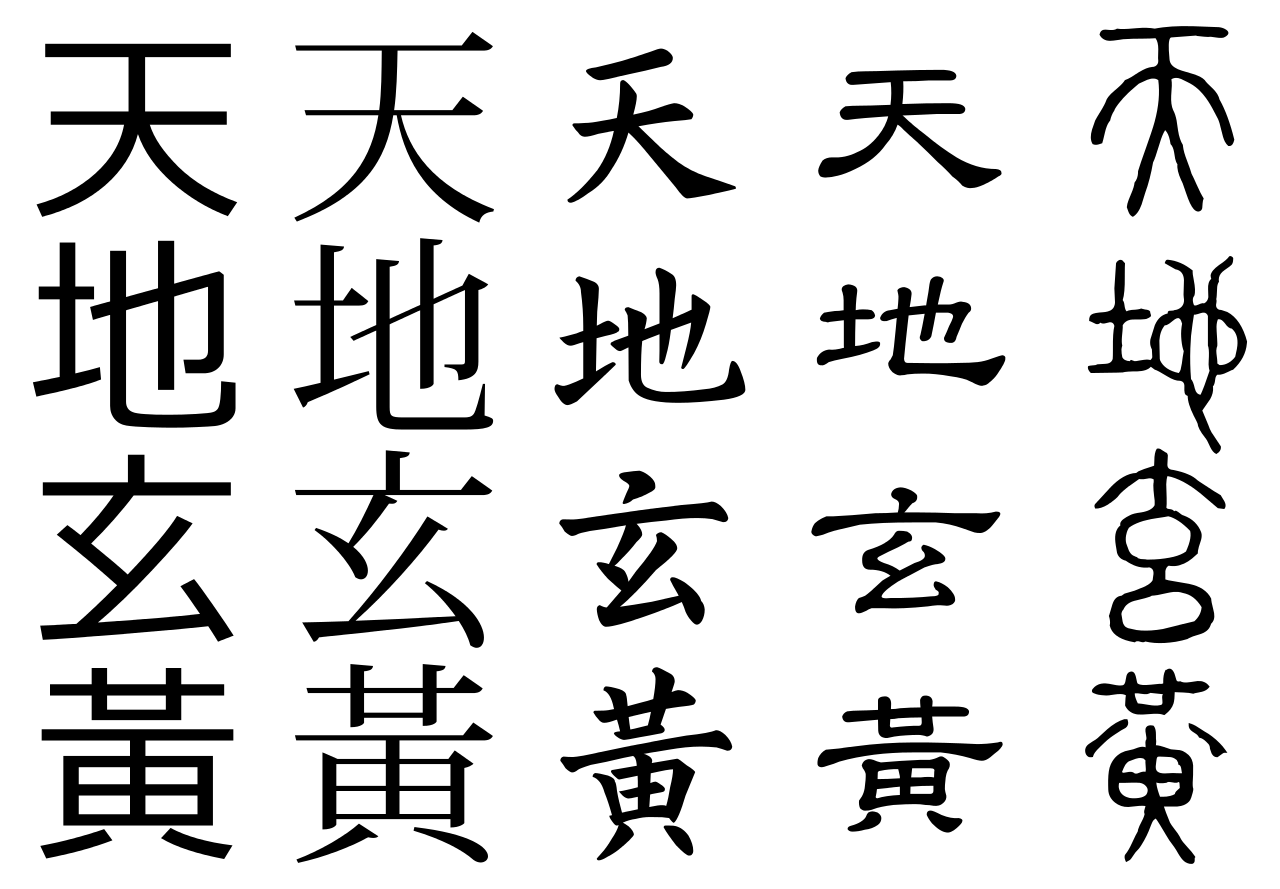

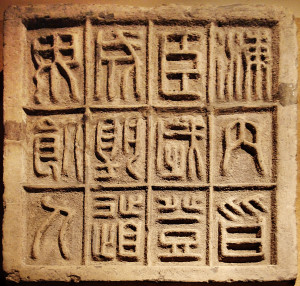

An old writing system

Probably one of the first things most people think of when they think of Mandarin is it’s unqiue writing system. Mandarin (like Cantonese) uses a character-based writing system, whereby characters represent whole words or parts of words. In total, there are approximately a staggering 50,000 characters, but most literate adults only know around 8,000 of these (which is a similar vocabulary to people elsewhere around the world).

Though in Mainland China these characters underwent simplification last century (which is why they are listed as ‘Simplified Chinese’), their roots can be traced back as far as the 2nd millennium BC. They have undergone considerable changes since then, but many basic features have been retained. Many of the early forms of characters were based on pictorial representations of what they were expressing, which is something that can also still be seen in many characters today.

A young language

Despite these ancient roots, modern Mandarin itself isn’t quite as old. In fact, Mandarin as we know it today is actually less than a century old. Before Mandarin, there was Guanhua (or ‘Official speech’), which was used in late imperial China by the educated elite. Although speakers of Guanhua could communicate quite easily by writing, pronunciation of the spoken form was never standardized, so many speakers brought along their own regional dialects and accents to the language when they used it. The majority of China, at this point, simply spoke their local language or dialect.

Mandarin, known as Putonghua (‘common language’) grew out of Guanhua. A serious of meeting by linguists and officials in the early and mid-twentieth century helped formally create China’s new lingua franca. The new language was based on the pronunciation of Beijingnese and the dialects of this spoken across north-eastern China, and used grammatical features from literary Chinese.

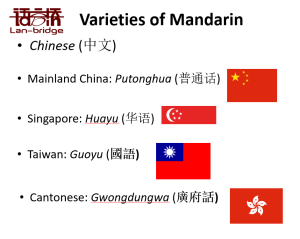

Which Mandarin?

Though the Mandarin in Mainland China is known as Putonghua, elsewhere is has different names. For example, in Singapore it is known as Huayu, and in Taiwan, Guoyu. Besides still using traditional (as opposed to simplified) characters, Huayu and Guoyu also have a few subtle features that are different from Putonghua (words, phrases, etc), however, they are all the essentially the same language: Mandarin.

A challenge to learn?

We have previously discussed how some non-Chinese found learning Chinese. Besides the large number of characters, another well-known feature is that Mandarin is a tonal language. Tonal languages are more common in Asia than Europe (where there are none), and seem like a challenge to many people when they first encounter them. However, Mandarin only has 4 stressed and one unstressed tone; Cantonese, for example, has nine. (Tones usually take only a few months to learn before advancing on to the next stage of progression. )

Moreover, the grammar in Mandarin is relatively simply, with relatively uniform rules, no genders, and simple additional syllables that indicate tense regardless of the verb. This goes part of the way in compensating for the time needed on learning (and then mastering) the characters and tones!

Follow us on WeChat