- +44 (0)20 8334 8266

- uk@lan-bridge.com

- 中文

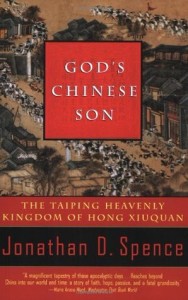

God’s Chinese Son by Jonathan D. Spence – A Review

China has a wealth of history that often makes for fascinating and surprising reading. The Taiping Rebellion (1850 – 1864) fits both of these categories perfectly. Firstly, because of the sheer scale of this event: in just 14 years, the rebellion lead to the deaths of up to 20 million people, making it technically the most catastrophic event of the 19th century. Secondly, because of the bizarre nature of the event: A failed Chinese scholar gathers followers by declaring himself the (second) son of God and leads a rebellion that very nearly overthrows the ruling Qing empire.

Jonathan D. Spence is one of the most distinguished and respected China historians alive today. His books cover a range of subjects (in both the topic and imperial sense of the word) across what can be loosely termed modern China, if we are to accept that period as starting roughly during the decline the Ming Dynasty in the first half of the seventeenth century.

Spence wanted to be a novelist before becoming a historian, and this is immediately and abundantly clear when you pick up any of his books, which all display his gift for narrative and eye for interesting details. God’s Chinese Son is no exception. Spence not only gives us a biography of the rebllion’s leader, Hong Xiuquan, but also gives the reader a vivid picture of the story’s background – of everyday life, trading, foreigner powers, politics, war, and much else in China during mid-nineteenth Century.

Examinations and visions

In the mid-nineteenth century China was at a relatively low point in its history. Indeed, today many Chinese today often label the whole century ‘the century of humiliation’. The Qing Empire was suffering from a range of problems: from aggressive foreign powers encroaching on it, to economic problems, banditry and internal political conspiracies.

It is in this context that Hong Xiuquan, a twenty-two-year-old married scholar from a village in Southern China, fails the imperial exams for a fourth time and falls seriously ill shortly after Chinese New Year in 1837. Neither of these events were particularly unusual at this time: only 1% of candidates successfully completed all stages of the imperial exams and unpredictable illnesses were a part of life.

It is whilst he is on death’s door that Hong has his vision that could compete with Paradise Lost for epic scale. Roughly summarised, it involved Hong ascending to heaven where he met his father (who has a golden beard) and older brother, battles demons down through thirty two layers of heaven (they end up being driven onto the thirty third: earth), rests, and then is sent back to earth by his father to continue his battle with the demons. The dramatic consequences of this vision itself compete with it for epic scale.

The third coming

Hong claimed that he only fully understood his vision a shortly afterwards, when he came into contact with Christianity via some books given to him by his cousin. He now realises that the father and elder brother in his vision were God and Jesus, and begans travelling and preaching in southern China, briefly coming into contact with foreign missionaries. This latter experience helps him learn more about Christianity, but he is disappointed when one American pastor refuses to baptise him, so moves on again.

Preaching a strange admixture of Christianity and his own self-serving myth, by 1850, Hong has amassed over 10,000 followers. He evidently had a gift for finding converts, especially amongst aimless bandits, disaffected chancers, a poverty-stricken peasants with few other opportunities in this society. His vision is codified in texts and rules taught to these new members of his self-declared kingdom, and includes edicts that order the radical segregation of men and women (including married couples) – all men and women, that is, except himself and his growing number of concubines: “Men or women who commit adultery or who are licentious are considered monsters; this is the greatest possible transgression of the Heavenly Commandments.” The punishment for this transgression amongst his followers was death.

Marching towards the promise land

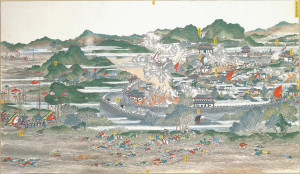

Harried by Qing troops, Hong had to guide his growing base of followers on through southern China’s varied landscapes, as they looked for a new base and as-yet-unspecified promise land. By this point, there are newly appointed “kings” in positions of authority under Hong, who command different parts of the Kingdom’s armies and populations. A combination of fanaticism, organisation and luck helps them on their journey. During this period, the battles and travails of the Taiping followers are described in an eloquent and fast-paced manner by Spence, who proves to be an excellent guide through the chaos of these ferocious scenes:

“…Quanzhou [a small city] is strongly guarded, but since it is not the Taping goal, their troops march and sail past the walls. In their midst, comfortable in his ornamental sedan chair, sits Feng Yunshang, the South King, the closest friend of Hong Xiuquan… Idly, a Qing gunner on the Quanzhou walls takes aim at the gaudy target and fires at the unseen passenger within. The shot has a deadly accuracy. The ball smashes through the chair’s ornamental coverings, seriously wounding Feng….

…. News of Feng’s mortal wound spreads unstoppably through the ranks, and the Taiping forces seem to act as one. Breaking their march, massing around the city walls, for over a week the Taipings launch assault after assault, whilst the neighbouring Qing commanders, scared of the Taiping ferocity, linger in their camps and refuse to give the city aid, despite the anguished pleas of the city’s magistrate, written with his own blood.”

Within two days, the Taiping have broken through the city’s walls and massacred everyone within them, before resuming their march.

The Heavenly Kingdom’s Earthly Paradise: Nanjing

Spence details how the Taiping army and its followers eventually end up in Nanjing, which Hong declares to be the capital of his new heavenly kingdom. I won’t go further than detailing this for fear of essentially ‘ruining the plot’, because that’s how enjoyable reading Spence’s work often feels. The facts are ample and well-presented, but there is rarely a dry moment as this story – like the marching Taiping army- rumbles on towards its climax.

What is worth illustrating is how the details Spence introduces helpfully convey some of the complexities of the times. Take, for example, the mysterious Irishman who joins the Taiping as a mercenary in 1856. Spence writes:

“The presence of an Irishman in the Taiping base areas in 1856 can be explained by the desperate nature of the times. The strict neutrality laws that the diplomats try and follow cannot prevent a certain number of rootless men from drifing into the Taiping camp to offer their services to the Heavenly King. From the earliest days of 1853, Westerners have been selling guns and ammunition to the Taiping, along with their services.”

We do not know this Irishman’s name, but thanks to his account we get a glimpse into how the Taiping Kingdom was run, from its trading and punishment practices to signs of the inner intrigues that occurred within the ranks of the powerful. By introducing this account at this point in the story, Spence wonderfully highlights several aspects that were at play simultaneously, from the foreign powers relationships to the Taiping, to the everyday reality and political machinations of its society.

Spence at his finest

It is incredible to think that the events described in this book overlapped (in time) with and surpass (in scale) the American civil war, yet remain largely unknown outside of China. This book is a great introduction to that history, and worth reading not just because of the events it describes, but also because of the background it gives. Spence is indisputably one of the finest historians and writers to ever take up Chinese history, and English-speakers in particular can consider themselves fortunate that he did.