- +44 (0)20 8334 8266

- uk@lan-bridge.com

- 中文

‘May Your Majesty Be Pleased That The Bible Be New Translated?’

Until the 16th century, Christian England didn’t have an official English bible. Dissidents who translated or disseminated such a thing often paid the ultimate price for doing so, even escaping the country couldn’t always save them from this fate.

To most of us living in the early 21st century, perhaps it is strange to contemplate that what was considered to be a book written by God Himself was inaccessible to most of the population. Compulsory attendance at church meant being preached to about the keys to mortality, morality and beyond in an incomprehensible language from an incomprehensible book. But perhaps in this illiterate, superstitious and class-based society, most people didn’t frame the situation in this way, and were merely more at peace with mystery. It was largely accepted that the Lord’s Words were too sacred to be translated by meager men (a very convenient fact for those in power, who controlled this knowledge). However, with the English Reformation, this state of affairs slowly began to change, and as with elsewhere in Northern Europe there was growing pressure for the bible to be written in the language of the people.

In the late 12th century Wycliffe’s Bible appeared, and was promptly banned and burnt (as was the exhumed corpse of its eponymous head author/project leader a few decades later). Next, the incomplete Tyndale Bible appeared (illegally) in 1536 (more about that in a couple of weeks here). Shortly afterwards, the Great Bible was authorized by Henry VIII in 1539, followed by the Geneva Bible (1560), and then the Bishop’s Bible (1568). The reason behind many of these different translations was political. The Geneva Bible, for example, was full of subversive annotations and choices of words that clashed with the ruling classes’ ideology, hence why the Bishop’s Bible removed these (changing the word ‘elder’ to ‘priest’, for example). But it wasn’t very popular, and was seen as inferior to the Geneva Bible, which was outselling it. (One famous example of its lack of quality is where it translated ‘cast thy bread upon the waters’ as ‘lay thy bread upon wet faces’.)

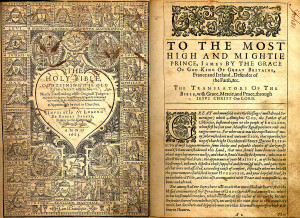

When King James VI came to power, however, a suggestion was given to him – the wording of which gives this article its title. A new translation, James thought, would give the country a bible that was to be both more accessible and ideologically correct, and would help unite the increasingly polarised society (a polarisation which erupted into civil war during his ill-fated son’s reign). It was to be known as the Authorised Bible, or King James Bible.

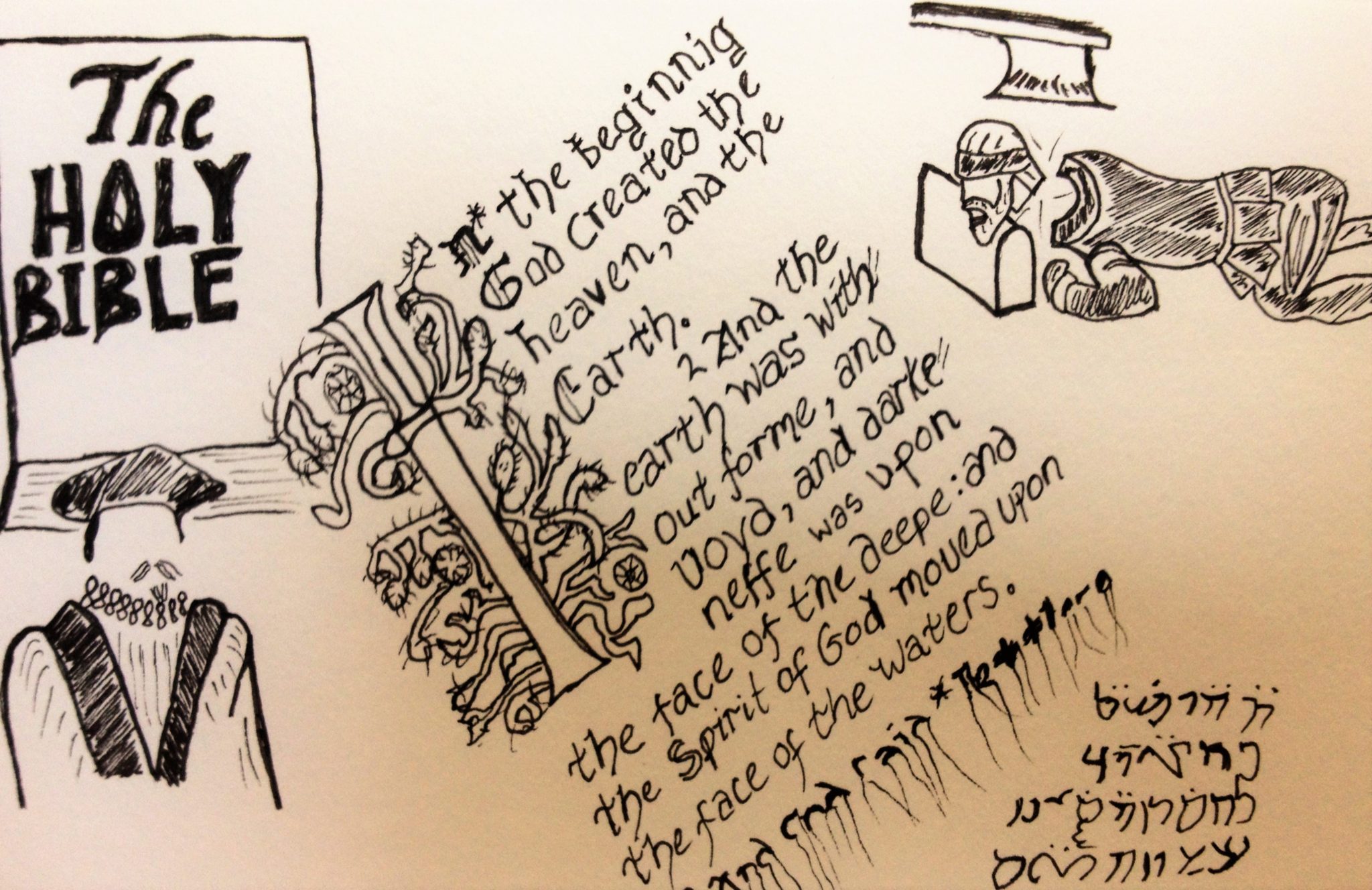

James assembled 48 of the country’s finest academics into 6 teams (each with a director) to translate the 66 books of the bible. They were to build on the previous translations as well as compare the text to the original Hebrew, Greek and Aramaic sources. This was an enormous undertaking, but never before had so many experts been mobilised. The whole project was overseen by the Church of England’s higher-ups, and ultimately had to be authorized by James, who also set the rules for it. We don’t know who all the translators were, but those that we do know give us an idea of the formidable learning these men had. The chief translator, Lancelot Andrewes, for example, was Master of Pembroke College, Cambridge, and spoke fifteen modern languages and six ancient ones.

One of the key rules for the translation stated: “The ould ecclesiasticall words to be kept viz. as the Word Churche not to be translated Congregation &c.” Anyone reading this at the time would have immediately understood the implications of this rule. ‘Churche’ clearly emphasises the official state institution, whereas ‘Congregation’ merely means a group of believers. What would people think –what ideas might they get?- if these two words were exchanged in 1 Timothy 3:15, for example: “But if I tarry long, that thou mayest know how thou oughtest to behave thyself in the house of God, which is the church of the living God, the pillar and ground of the truth.” James clearly favoured stability and continuity over the more radical implications of the Reformation, and so regardless of what word more accurately reflected the original, ‘Churche’ was to be used.

An older, slightly archaic -and therefore more authoritative sounding- language was applied in this new translation. Rhythm, memorable phrasing and a poetic cadence were favoured over precision and fidelity to the original texts. Comparing this translation with its contemporaries or even other modern translations gives a good idea of how this works in practice. Here are the dramatic opening words of the most pessimistic and existential of the bible’s chapters, Ecclesiastes:

King James Bible:

“Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities; all is vanity.

What profit hath a man of all his labour which he taketh under the sun?

One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever.

The sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down, and hasteth to his place where he arose.”

Good News Bible:

“It is useless, useless, said the Philosopher. Life is useless, all useless. You spend your life working, laboring, and what do you have to show for it? Generations come and generations go, but the world stays just the same. The sun still rises, and it still goes down, going wearily back to where it must start all over again.”

The finished translation appeared in 1611, four years after it was commissioned, and for the next 270 years, it was the official bible of the Church of England. It is considered by many as one of the greatest and most influential works in English ever written, a book central to England’s culture. Owing to the skill of its translators in sticking to James’ rules (and no doubt the religiousness of the nation at the time), many of its phrases entered the English language, where they remain today. Here are just a few: ‘a law unto themselves’, ‘den of thieves’, ‘eye for an eye’, ‘money is the root of all evil’, ‘the blind lead the blind’, ‘a stumbling block, ‘from strength to strength’, ‘fallen from grace’, ‘eat, drink and be merry’.

To give an idea of how at least some people view the Kind James Bible, I will give the last word to one of its most enthusiastic advocates, historian Adam Nicholson, who writes in When God Spoke English: The Making of The King James Bible: “If you think of the bible as the greatest creation of seventeenth century England, a culture drenched in word rather than the image, it is easy to see it as England’s equivalent of the great baroque cathedral it never built, an enormous and magnificent verbal artifice, its huge structures embracing 4 million Englishmen, its orderliness and richness a kind of national shrine built only for words.”

Further reading:

The King James Bible

When God Spoke English: The Making of The King James Bible