- +44 (0)20 8334 8266

- uk@lan-bridge.com

- 中文

Nabokov Translating Pushkin

Alexander Pushkin is considered by many to be Russia’s greatest poet. In fact, many consider him one of the world’s greatest poets, second only to Shakespeare. A huge factor in his success was the brilliance of his use of the Russian language. One of his biographers, Elaine Finkelstein, writes: “To imagine his qualities as a poet, a reader of English literature would have to invent a writer with the facility of Byron, the sensuous richness of Keats and a bawdy wit reminiscent of Chaucer.” But even if non-Russian speakers can have Pushkin’s greatness explained to them, can they ever truly understand how great he is by reading his work in translation?

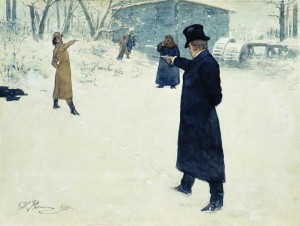

Pushkin’s most famous work is Eugene Onegin. This novel-in-verse was written between 1825 and 1832, and published in full in 1833. It tells the story of a bored young man, his rejection of love and later regret of this, and his friendship and then duel with a fellow aristocrat. Woven into this plot is a great tapestry of observations, witticisms and satire – all told in an unusual rhyme scheme using iambic tetrameter and some of the finest language ever produced in Russian.

Enter Nabokov

In the 1960’s, Vladimir Nabokov, the only writer to simultaneously hold the position as a giant of both Russian and English literature, published an English translation of Pushkin’s masterpiece. In the decade between its conception and reception, he had formulated and then conscientiously applied a distinct translation methodology for this nuanced and unique text.

Nabokov believed that there were three routes a translator of poetry could choose from: a loose translation with paraphrasing and additions added according to the whim of the translator; a basic translation, with the words in the same order as the original – much like what you get with today’s online translator apps; or, “[r]endering, as closely as the syntactical capacities as another language allow, the exact contextual meaning of the original.” He chose the third route.

Enter Wilson

The debate surrounding whether this was the correct choice wasn’t merely academic – it created a rift between Nabokov and his (until-then) close friend Edmund Wilson. Wilson, a well-known literary critic who had helped introduce Nabokov to the American literary world, claimed in an article entitled ‘The Strange Case of Pushkin and Nabokov’, that Nabokov’s translation “lacked common sense” and that “he seeks to torture both the reader and himself by flattening Pushkin out and denying to his own powers the scope for their full play.”

Nabokov’s riposte came in an article entitled, ‘The Strange Case of Nabokov and Wilson’, where he rebutted many of Edmund’s points and expressed his dismay at his friend’s “mixture of pompous aplomb and peevish ignorance,” which he felt was “certainly not conducive to a sensible discussion of Pushkin’s language and mine.”

Exit rhyme or reason?

Certainly Wilson’s attempts to criticise Nabokov’s Russian were doomed to fail from the start. But was he right to criticise the translation technique Nabokov used for Eugene Onegin? This question, which cuts to the core of what translation is, should be left for readers to decide.

It is relevant outside of the world of literature, too. For practical everyday use, translation’s purpose is straightforward enough – but not so straightforward that machines can consistently do it with accuracy. Subtlety, irony, nuance, allusions and alliteration are just some of the characteristics that often vanish in translation. When companies want to market in new languages and cultures, more specialist work is needed to produce more appropriate language. Sometimes, holding together accuracy can only be done at the expense of other aspects.

It is, Nabokov noted, “mathematically impossible” to retain rhymes and accuracy in the translation of a poem. When translating marketing material, brand names, slogans, etc., then, we need to appreciate that it is mathematically unlikely to encapsulate everything from the original language, which is why the use of a high-quality translator is essential.

Let’s give the final word to Nabokov, who wrote in his introduction to his version of Eugene Onegin: “Pushkin likened translators to horses changed at the post houses of civilizations. The greatest reward that I can think of is that students may use my work as a pony.”

Further Reading:

Pushkin by Elaine Feinstein

Eugene Onegin: A Novel in Verse by Alexander Pushkin (trans. by Vladimir Nabokov)

Strong Opinions by Vladimir Nabokov

‘The Strange Case of Pushkin and Nabokov’ (New York Times, 1965) by Edmund Wilson

‘The Strange Case of Nabokov and Wilson’ (New York Times, 1965) by Vladimir Nabokov