- +44 (0)20 8334 8266

- uk@lan-bridge.com

- 中文

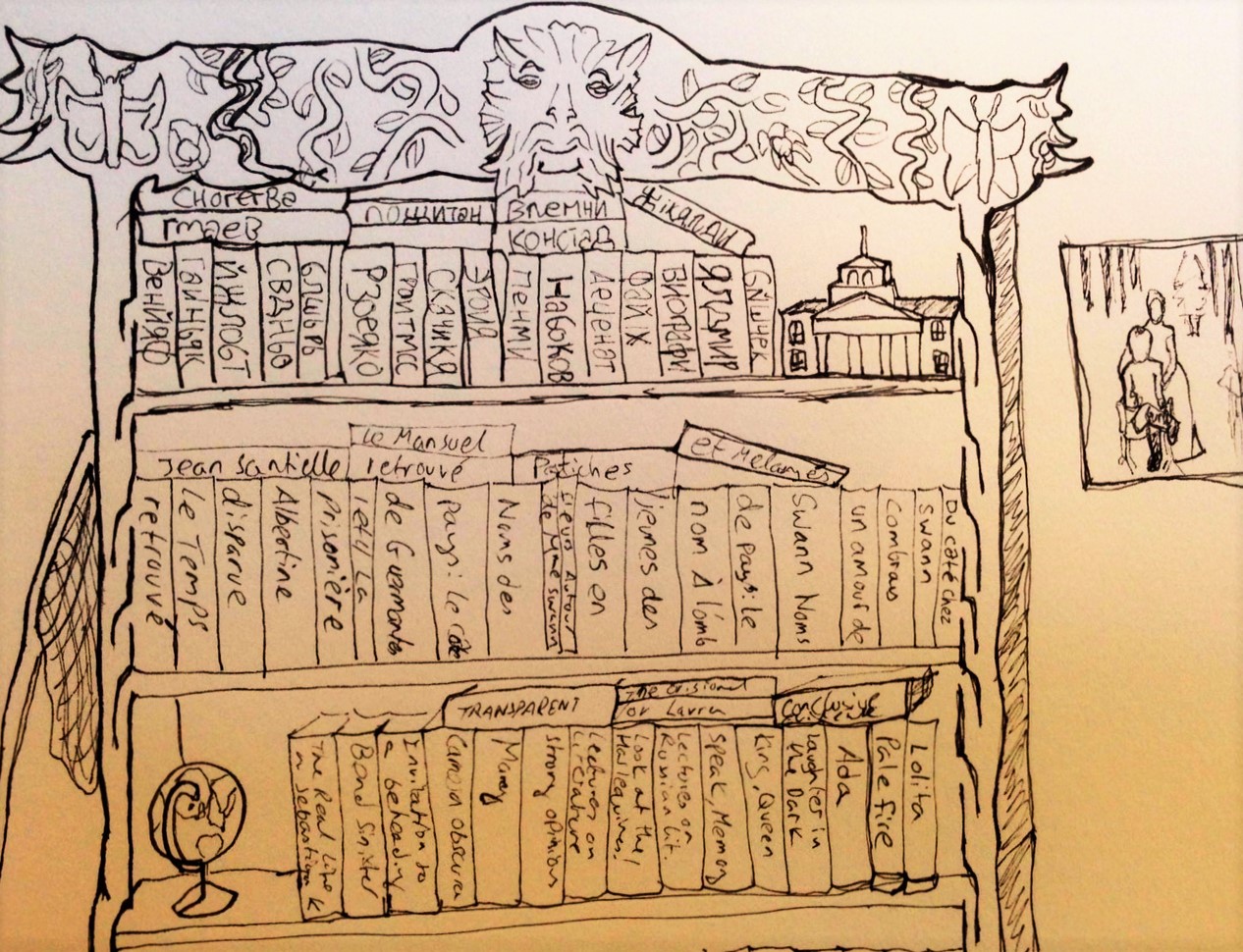

Nabokov’s English

Vladimir Nabokov, born in St Petersburg in 1899, learned to read English before Russian. His family hired a series of foreign nannies and tutors, so that, alongside his brothers and sisters, he was brought up speaking 3 languages – Russian, French and English (‘I was a perfectly normal trilingual child in a family with a large library’ he later remarked). His father had experienced a similar upbringing, and could himself speak 4 languages. As his son notes, the elder Nabokov’s linguistic skills were extraordinary: “From 1905 to 1915 he was president of the Russian section of the International Criminology Association and at conferences in Holland amused himself and amazed his audience by orally translating, when needed, Russian and English speeches in German and French and visa versa.”

Not long after the Nabokovs fled Russia, Vladimir (the son) went to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied medieval French poetry. After graduating, he moved to the then centre of the Russian émigré community, Berlin, where as well as writing poetry, plays, short stories, novels, articles and crosswords (which he may well have invented in Russian), he also translated C.S. Lewis’ Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland from English to Russian.

With the Nazi’s rise in Berlin in the 30’s, Nabokov began looking for an escape from Germany. He ended up in Paris, where he tried his hand at writing in French. The result was ‘Mademoiselle O’, a superb short story about one of the many Swiss nannies hired by his parents to help their children acquire French. Later on, he translated this story into English and used it for a chapter of his autobiography, Speak, Memory (which he then translated into Russian).

Whilst in France, the Nabokovs (Vladimir, his wife and young child) began to look for ways to leave continental Europe. It was during this time he tried his hand at writing in English. In 1939 he wrote The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, hoping that it would bolster his eligibility for a teaching post at Cambridge. The novel is about the narrator’s search for his novelist brother, ‘[who] had two periods, the first -a dull man writing broken English, the second – a broken man writing dull English’ (as a fictitious reviewer in the novel states). This novel shows a masterful grasp of English – better than most native speaking English novelists are capable of. However, there are some very faint trances of his non-native origins:

‘… but although the two women were very old friends (that is, they knew more about each other than each [either] of them thought the other knew)…’

‘And you could not suggest any way of finding her?’

‘None,’ he said.

‘Mutual [common] acquaintances?’

‘…there were two more persons drinking tea at the round table which we were seated [sitting] – a man from my office and his wife, both of whom Sebastian had ever known [neither of whom Sebastian knew]…’

Unfortunately, Nabokov didn’t secure work in Cambridge. So, as the Germans approached Paris, he was forced to flee once again. With his wife and son he left for America, where he found work teaching Russian in universities. This gave the 40-year-old writer a dilemma – with his Russian émigré audience further dispersed, and his writing still banned in Russia, who was he to write for? He decided to keep up what he had begun with The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, and continued writing for an English-speaking audience. He wrote a poem, ‘Softest of Tongues’, at this time:

But now thou too must go; just here we part,

softest of tongues, my true one, all my own….

And I am left to grope for heart and art

and start anew with clumsy tools of stone.

Those ‘clumsy tools of stone’ proved to be more capable than the tone of the poem would suggest. Their most famous accomplishment was, of course, Lolita, published in 1955. This remarkable novel was famous not only for its shocking story-line, but also for how well it was written (‘You can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style.’ Humbert the narrator declares at the beginning of the novel). Stylistically, Lolita is one of the finest works of English literature ever written. Just about every page is filled with writing that most of us can never hope to be capable of. For example: ‘With the quiet murmured order one gives a sweat-stained distracted cringing trained animal even in the worst of plights (what mad hope or hate makes the young beast’s flanks pulsate, what black stars pierce the heart of the tamer!) I made Lo get up…’

Lolita (1955)

Yet as undoubtedly well-written as Lolita is, reminders that his English is not fully native can be found if we look very closely (as closely as we need to look to find his various hints and puns):

‘I quietly suggested she comment her wild talk.’

‘…the anything but distracted swimmer was finishing to tread his wife underfoot.’

‘It was then that began our extensive travels all over the States.’

‘In result of this venture…’

‘I cannot well explain…’

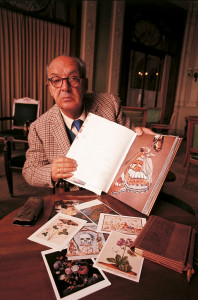

After Lolita’s success, Nabokov did what he had long-dreamed of doing: quit his day job, and moved to a hotel in Switzerland, where he not only continued writing, but also translating (as we saw the other week). Aside from Eugene Onegin, his biggest task in this area was translating his own work. He decided to translate his earlier Russian novels into English, and his later English works into Russian, as well as supervising French (and later, Italian) versions of his novels. He done much of this himself, but also used outside and inside (family) help. Later, his son Dmitri became his main translator (after a near-fatal car crash in the decade following his father’s death, Dimtri decided to fully dedicate himself to completing this task).

Nabokov in Switzerland, 1969.

When writing about Nabokov, it is often best to give him the last word. In his lecture ‘Russian Writers, Censors and Readers’, he strongly emphasises that it was his cultured upbringing which gave him the chance to fulfill his potential: “…if my fathers had not been good readers, I would hardly have been here today, speaking of these matters in this tongue.”

Further reading:

By Nabokov:

Lolita

Lectures on Russian Literature

Speak, Memory

The Real Life of Sebastian Knight

Other:

Nabokov: The American Years by Brian Boyd